Do you have children in your class who fly off the handle for no apparent reason? Does something as simple as a pencil being knocked off their desk send certain children into a rage? This overreactive behaviour may be driven by toxic stress?

THE EVOLUTION OF STRESS

Stress is our physiological survival response to threat. The stress response is what often kept us alive as primitive man. As hunter-gatherers, when confronted by a woolly mammoth, we either needed to run away as fast as we could or fight with all our might. To mobilise our body for action our primitive brain flooded our body with stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline) causing our heart to beat faster, pumping oxygenated blood to our muscles. Nowadays, we no longer need to run away from woolly mammoths, but our physiological stress response remains the same. This fight-flight stress response not only ignites our ‘primitive brain’ but shuts down our ‘thinking brain’ making it impossible for us to think or respond rationally.

Harvard University Centre on the Developing Child refer to three levels of stress; positive, tolerable and toxic. Positive Stress occurs as the result of brief increases in heart rate and mild elevations in stress hormones. This can sometimes help motivate us to reach our goals and can even boost our memory e.g. when sitting exams. Tolerable stress is the result of a more severe event where the stress response is more prolonged and intense but, when supported and co-regulated by a caring adult, the child is able to return to a neutral state, which contributes to the development of healthy stress response systems; something vital for our future mental and physical well-being.

WHEN DOES STRESS BECOME TOXIC?

There are times when stress can be problematic. If/when a baby suffers neglect or abuse at an early age, the stress response can affect the developing brain architecture and brain chemistry. Because most brain development happens in the first four years of life, trauma during this time has the most damaging effect on development. When cortisol floods an infant’s brain, this ‘cortisol wash’ causes changes in brain structure that can have lifelong implications in behaviour, learning and health, and lead to what is known as ‘Toxic Stress’. Toxic tress can also happen in later childhood and adulthood and effects will differ depending on the age of the person and the stage of brain development.

IMPLICATIONS FOR BEHAVIOUR

- Overreactive behaviour and increased aggression. The over-activation of the primitive brain, strengthens the neuronal connections that lead to the Fight-or-Flight response; these children are living in constant high-alert and are unable to control their behaviour, or calm themselves down.

- Hyper-vigilant to their surroundings. Unable to settle, always on the look-out for perceived danger and in survival mode.

- Difficulty with relationships/interacting. Some children may distrust others which can lead to difficulty with friendships, as well as difficulty with authority or criticism from adults.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH

Research also shows that prolonged stress can have serious health implications throughout life, including:

- Compromised immune system. Children may have more stomach aches, trouble fighting off infections etc. and therefore have worse school attendance.

- Mental health disorders, such as depression.

- Health problems later in life such as heart disease (particularly atherosclerosis – the accumulation of fatty plaques inside blood vessels) and increased risk of cancer.

IMPLICATIONS FOR LEARNING

Toxic Stress has huge implications for learning, not only as a result of the behavioural effects, but also how it affects brain architecture. Brain imaging shows that vital connections in the frontal cortex (the ‘thinking brain’) and hippocampus are not made or even shrink, leading to impaired learning and performance in school. Furthermore, the amygdala (the area responsible for processing feelings and emotion) becomes more developed, leading to increased anxiety and vigilance. So, for those children suffering from Toxic Stress, it is a double-edged sword.

They may have difficulty in a number of areas:

- Cognitive delay – they may have problems with their working memory, as well as their executive function (planning and problem solving).

- Maintaining focus – they may be easily distracted.

- Poor listening skills.

- Get frustrated with difficult tasks.

Remember, these children are constantly just trying to survive and therefore learning is not a priority.

WHAT CAN WE DO TO HELP?

The first thing we need to do is to recognise why they are behaving like this. Having an understanding of what is going on in the child’s brain will help us respond more empathically. They are not behaving like this deliberately. So instead of thinking “What’s wrong with you?”, you may want to think “What’s happened to you?”

Brain plasticity means that the brain architecture is not fixed and is capable of change. By implementing the right strategies we can help build new connections and thus a healthier brain.

- Supportive stable trusting relationship. Can you provide a Key Adult? By acknowledging and accepting a child’s feelings it lets them know you care. All children need someone in their lives that say, “I believe in you…you’re ok”. If this doesn’t happen at home, then it can happen in school. This can give a child security to heal and build new brain pathways which are positive. With good care, we can improve brain growth, whilst also giving the child that crucial sense of safety and belonging.

- Provide a safe place for the child to talk. Having a ‘Listening Ear’ or Key Adult can provide a place where the child knows it’s okay to talk. These children need somewhere to go to allow their brain and body to calm down.

- Co-regulation/Emotion Coaching. These children are likely to have difficulty with self-regulation because they may not have experienced co-regulation of their emotions when they were young. It’s therefore important to talk about feelings and emotions to help them to recognise and manage ‘big’ emotions. Use reflective listening and empathy to label and validate the child’s feelings. Use problem solving strategies to recognise triggers, as well as help the child learn strategies to deal with problems or issues.

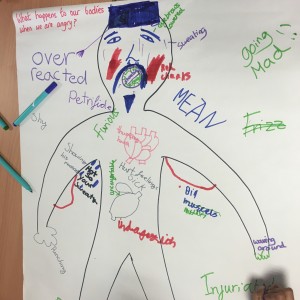

Teach children about their brains. Children love to learn how their brains work. Teaching them to understand the physiological basis for their behaviour helps them to manage their emotions.

Teach children about their brains. Children love to learn how their brains work. Teaching them to understand the physiological basis for their behaviour helps them to manage their emotions.- Drumming or Dancing. Children’s brains develop from the bottom up, so we need to address the issues arising from the ‘primitive’ brain first before we can help the ‘thinking’ brain. Dr Bruce Perry (Head of the Child Trauma Academy) states that “the only way to move from a super-high anxiety state, to a more calm cognitive state, is rhythm”. He believes this patterned, repetitive rhythmic activity, such as walking, drumming, dancing, singing uses brainstem related somatosensory networks which enables cortical thinking.

- Ways to calm and build the brain. This can change the damage done to the brain by the Toxic Stress. Dr. Lori Desautels describes how ‘focused attention practices’ are a neurological strategy for calming an angry and anxiety-ridden brain”. There are many ways you can calm the brain, such as mindfulness and deep breathing which causes oxygenated glucose blood to flow to our frontal lobes (taking just three deep inhales and exhales calms the emotional brain). She also describes how she begins class with a 90 seconds hand massage with children rubbing lotion into their hands.

Remember, you can make a difference in the life of every child you interact with every day.

Leave Your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.